2024

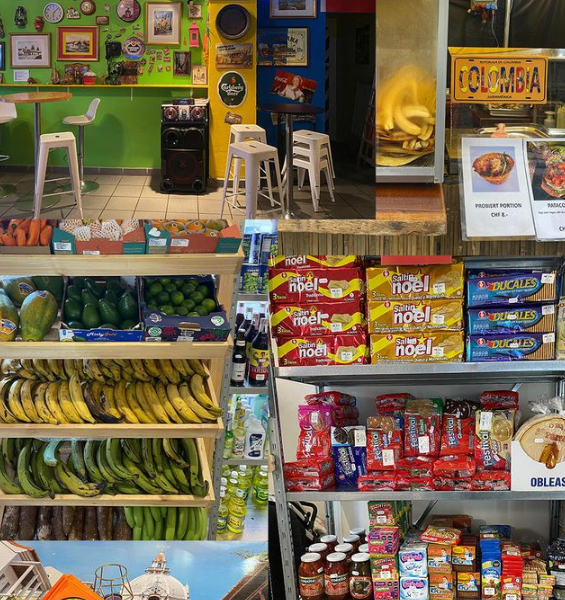

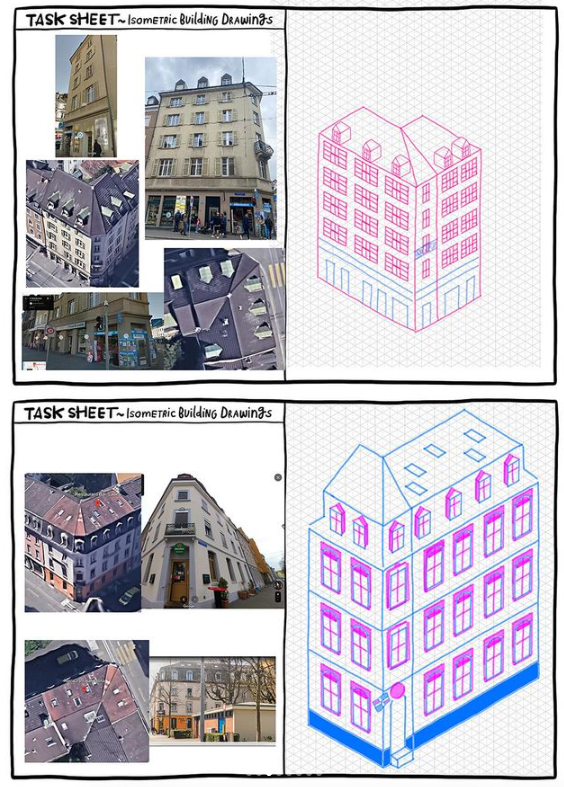

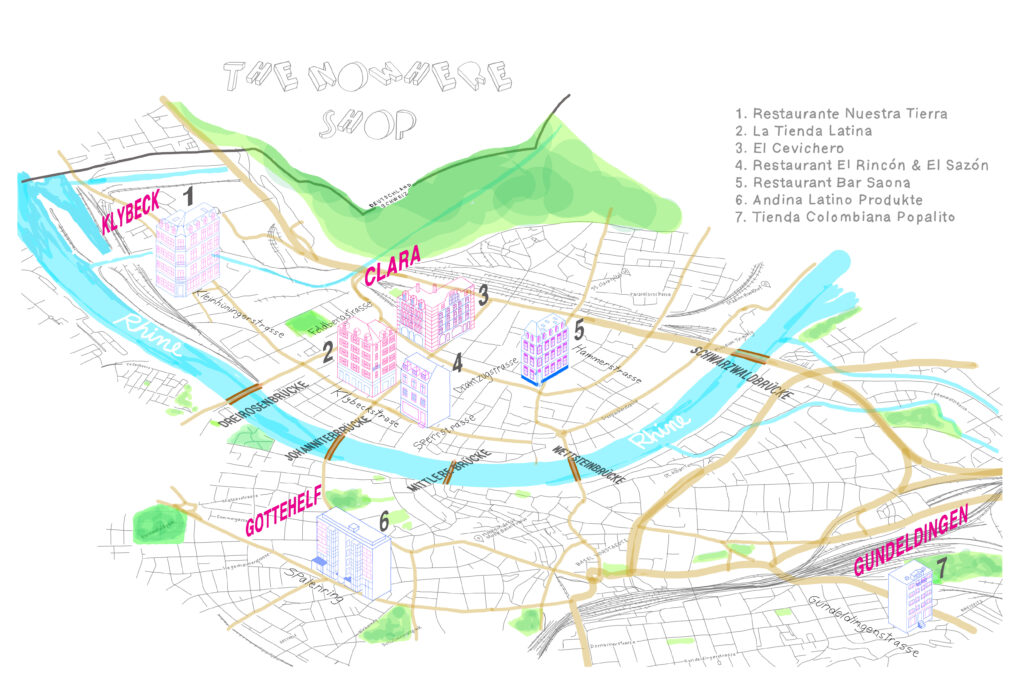

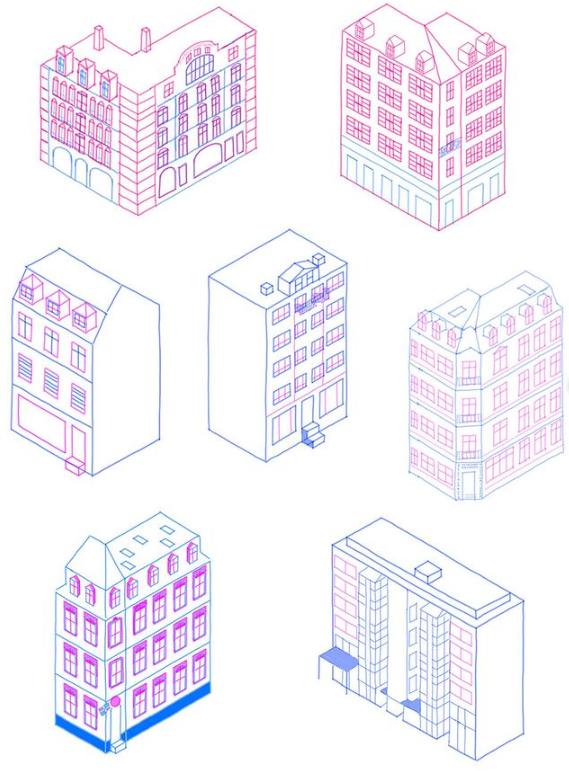

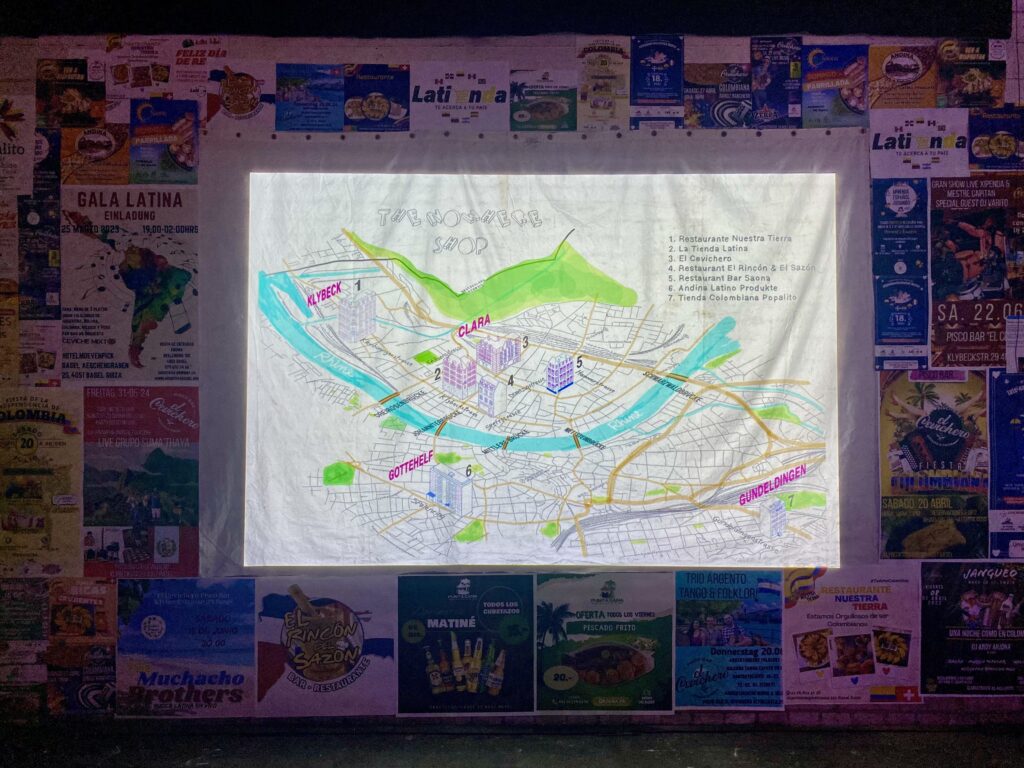

The Nowhere Latino Shop is the starting point of my master’s thesis project. I’m exploring multimodal narratives based on local Latino commercial establishments in Basel City. Through interviews and archival advertising materials, I research the graphic design and communicative appearance of these establishments, and how their best-selling products reflect nostalgia and stereotypes of their hometowns. The Nowhere Latino Shop is the first stage of an artistic and design research project that investigates the lack of a sense of belonging expressed by the owners. Additionally, it examines how these places, which showcase their culture, serve as focal spaces to engage with the ambivalence of integrating into the Swiss context.

Mixed media

Basel, Switzerland

The nostalgic places in the infrastructure of new beginnings

There are choices that were randomly assigned to everyone. Many aspects that shape us as living beings were not chosen with consent. We didn’t choose our mother tongue, skin color, socio-economic position, or sex, among other factors. As individuals, the organization of life occurs in random and unexpected ways initially, which profoundly influences our lifetime and societal structure. We were born on a random planet, in a specific location, which provided us with context and identity. Questioning our infrastructure is a privilege because not everyone has the opportunity to change the structures defined by social norms or patterns (Berlant, 2016).

WHAT MAKES HOME?

There is not a single answer. It’s a personal question related to feelings of comfort and security. However, reflecting on what constitutes home may lead to common conceptions for certain groups. Factors such as language, food, dancing, architecture, religion, etc., can all contribute to this notion. Dislocation can induce homesickness regardless of the circumstances of migration. It’s a crisis that challenges the infrastructure of identity. I want to explore how a city reflects the sense of belonging and also examine how nostalgia functions in constructing a sense of home in a foreign place through a creative project to connect with others.

As a migrant in a legal situation, I have the freedom to explore the new place where I live through walks, conversations, and sometimes as a customer, to identify various commercial establishments such as restaurants, supermarkets, bars, hair salons, etc., which reveal different origins and perspectives that are adapted or in the process of adaptation in Basel. I am curious about how nostalgia and feelings of displacement are invisible forces that shape home in a place where you were not born, and where it doesn’t entirely feel like home, yet somehow it does.

EVERYTHING WORKS

As a migrant, I feel guilty to be here. I’m very privileged in my country, and living here is not affordable or possible for most Colombians. Switzerland is idealized, and there are reasons for that. There are study and work opportunities, there is security, and as a woman, I don’t feel paranoid walking at night; it’s common to hear that ‘everything works.’ However, what does that mean?

To keep us alive with dignity, we need shelter, food, and a roof over our heads. There is a lifeworld of structures, invisible forces that sustain organizations of life, which change depending on the context. Moving to another place forces a body to expose itself, consume, and build relationships with others and the environment to integrate into a system. Experiencing displacement could be transitional and open new organizations of life, but it also conditions and sacrifices others.

I am from Colombia, a country often categorized as third world. However, my life there was very comfortable because I did not have to pay rent, my neighborhood was relatively safe, and I had a stable job and inherited income that allowed me to afford dining out and taking short trips on weekends. I was not perceived as a newcomer or someone from an exotic land. I did not notice my accent or worry about grammatical correctness in Spanish to communicate effectively. It’s an odd feeling, being judged for my skin tone, brown eyes, or black hair.

Nevertheless, I am a privileged migrant in a privileged country that I chose and I was allowed to have a temporary residence. I wasn’t compelled to relocate due to security, political, or economic reasons. It’s a luxury to be able to think about migration and explore the concept and infrastructure underlying displacement and the nostalgia it evokes, from both an academic and creative standpoint. Despite my feelings of guilt, I aim to unravel the motivations behind the desire to live in an unfamiliar place and explore the potential for new ways of living through the experiences of others who are also undergoing an adaptation process.

As a starting point, I want to shape the research by asking how these places portray an interpretation of their culture, both from where they originate and where they are located. Additionally, I am interested in exploring whether these places sell products that serve as identity icons but also expose stereotypes, while simultaneously serving as oasis for their communities.

Engaging in a participatory project presents a challenge, as it demands transparency with participants to establish agreements that validate the significance of the exploration. I position myself as a mediator, facilitating connections among participants and collective reflections on the infrastructure underlying nostalgia in a multicultural urban context. Through a series of creative practices that include structured workshops and participatory design activities to connect a shared understanding of the multifaceted dimensions of nostalgia within the urban landscape. I aim to delve into how these places shape the notion of home in a foreign land, where familiarity is juxtaposed with a sense of otherness.

REFERENCES

1. Berlant, L. (2016). The commons: Infrastructures for troubling times*. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 34(3), 393–419. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775816645989